Raw [Normalized] Data Now: Tim Berners-Lee and the Future of the Web

Tim Berners-Lee, inventor of the internet, recently spoke at the 2009 TED conference. His talk was an inspirational glimpse into the life of someone who has clearly never stopped exploring and always done what was intriguing to him – it just so happens that his road wound up providing a tremendous benefit to society.

Some highlights of the talk were Tim’s sheer joy at the notion that he had made an addition to a collaboratively edited map; a new Three. Word. Mantra (Raw Data Now); and a shoutout to a previous outstanding TED talk on the power of making data useful and universally accessible (sounds familiar).

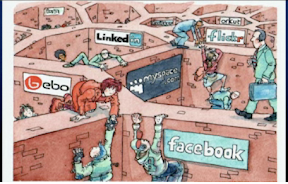

Tim also put up a cartoon that made fun of the fact that all of these different social sites (Facebook, LinkedIn, Flickr, etc.) exist in silos, incapable of fully interacting with one another.

This is certainly a problem that the major sites are aware of and are working to fix; Facebook, for example, allows me to import a feed of my activity on Picasa (Google’s photo storage/sharing service).

But it doesn’t quite cut it. Photos are a perfect example of my point. Let’s say I have an album, and I want to keep it on Picasa (or Flickr, or wherever) instead of Facebook because I don’t want the picture size reduced (or any other reason). However, I still want to tag my friends in that album, and if people make comments, I want those to appear below the pictures.

The current solution is broken – when’s the last time you clicked through on something like “John has uploaded new photos to Flickr” and left a comment on his picture, after finding it tagged with all of John’s Facebook friends?

The workaround hints at the solution. I have several photo albums that have “_facebook” appended to their names. These albums are duplicates or near- duplicates of albums that are stored elsewhere but that I wanted to share and tag using my Facebook network.

Such duplication of data should leave anyone who works with databases (myself included) banging your head against your keyboard right about now. ao;idsgja;sodijadosifj. That’s better.

We need to “normalize,” in database-speak (read: stop duplicating), the content that we put on the web. After all, it’s our content! Right now we’re jumping through all sorts of hoops because Facebook has our network but Flickr has more storage and better picture quality. Why should that matter? Why should we have to make this compromise?

Instead of duplicating and distributing content, it needs to be in one single place, accessible to those applications and sites that you give permission to. You provide the information; Facebook provides the social network, the display formatting, and the ability to easily allow others to make additions (e.g. comments) to that information. Your. Raw. Data.

It’s REST meets the social web.

Tim talked about how data is all about relationships (bing!). The most challenging part of all this is making it simple to manage these relationships. Let’s move away from photos for a second and talk about another piece of data that we would ideally keep in one place rather than duplicating it across multiple sites: basic profile information.

Things like name and email address are straightforward. Any site that is interacting with Your Raw Data probably requires one of these as their primary way of distinguishing an account. But what about something like “favorite books”? Or “professional experience”? I want the first to be on Facebook but not LinkedIn, and vice versa for the second. Or what if I want to have “homebrewing” on my list of interests on Facebook but replace it with “golf” on that same list on LinkedIn?

Connections are perhaps an even better example, and one that’s gotten more attention - I want to be friends with my co-worker on LinkedIn, but not so much on Facebook. How to manage those different relationships?

And to cite a far more useful example – Tim talked about databases for pharmaceutical companies and researchers, trying to find all the proteins with certain characteristics. One lab might do an experiment and determine that a protein does have the ability to do XY and Z - does that mean the connection should be made? What if another lab produces a conflicting result? Who decides whether it’s a valid connection?

While there are a ton of people working on the problem right now, none of the results I’ve used take the approach that I’ve outlined here. Many aggregate from the current smorgasbord, which is certainly the easiest thing to do, but not, in the long run, the most useful. If anyone is jumping out of their chair right now and interested in a little side project, let me know :-)

I’m going to cut this off here but hopefully will have more to write about on the topic soon. In the ultimate irony, these thoughts will be posted to my blog and then imported as a “note” to Facebook. Any comments written in either location will not be displayed in the other one.